“So now abide faith, hope, and love, these three. But the greatest of these is love.”

The Dirty South

On Black Tuesday, October 29, 1929, stock values plummeted on the New York Stock Exchange, sending the entire world into scramble mode. The “crash” officially and abruptly ended the roar of the 20s and ushered into its place and over its gravesite the moanful wail of the Great Depression, which would last the better part of the 1930s.

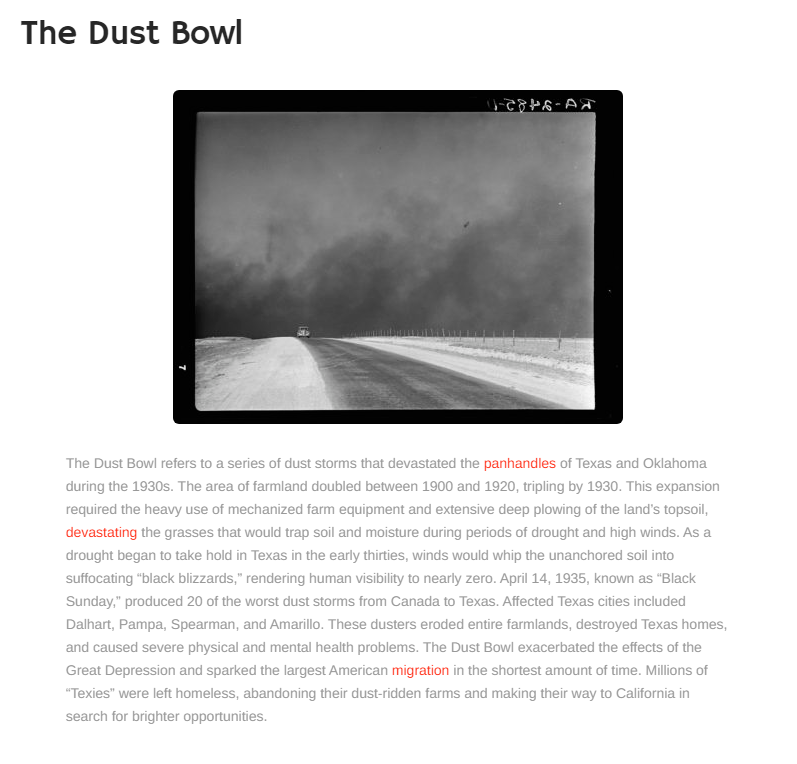

So devastatingly impactful on the American consciousness was the Great Depression that we have all but forgotten the equally – or even more – devastating Dust Bowl of the 1930s.

Following is an exerpt from the article, The Great Dust Bowl of the 1930s was a Policy-Made Disaster:

“Though the Depression still looms larger in the American mind, the Dust Bowl was no less traumatic or devastating for those who lived through it, and, like the economic crisis, it transformed American society as thousands of people lost their farms, their way of life, and, in some cases, even their lives.

Because the Dust Bowl is, for most people, a distant event, it might be helpful to get a sense of its massive scale through some facts and figures:

On a single day, April 14, 1935, known to history as Black Sunday, more dirt was displaced in the air (around 300 million tons) during a massive dust storm than was moved to build the Panama Canal.

Dirt from as far away as Illinois and Kansas was blown to points east, including New York City and states on the East Coast.

By 1934, it was estimated that 100 million acres of farmland had lost all or most of its topsoil to the winds.

During the same April as Black Sunday, 1935, one of FDR’s advisors, Hugh Hammond Bennett, was in Washington, DC, on his way to testify before Congress about the need for soil conservation legislation. A dust storm arrived in Washington all the way from the Great Plains. As a dusty gloom spread over the nation’s capital and blotted out the sun, Bennett explained, “This, gentlemen, is what I have been talking about.” Congress passed the Soil Conservation Act that same year.

In addition to the damage to the land through the erosion of topsoil, the Dust Bowl prompted thousands of farmers to leave their farms and move to the cities or to leave the area entirely and head out West, around ten thousand a month at its peak. So many of those who headed West came from Oklahoma that they became known as Okies. They were immortalized by John Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath.

The Dust Bowl affected 100,000,000 acres of farmland. The Texas Panhandle and western Oklahoma marked the epicenter of the crisis. Amarillo may have been in the heart of the matter, but Lubbock, just 123 miles south, was not spared. According to Texas Monthly, “During the typical Dust Bowl storm, 122 tons of dirt an hour blew through Lubbock.”

Plenty of folk up and left the Dust Bowl areas. At the height of the exodus, as many as 10,000 per month were loading their jalopies and heading west for California, in hopes of work on the farms and ranches there. Those who left were met by hard times and some by utter disaster. Those who stuck it out fared no better.

Faith…

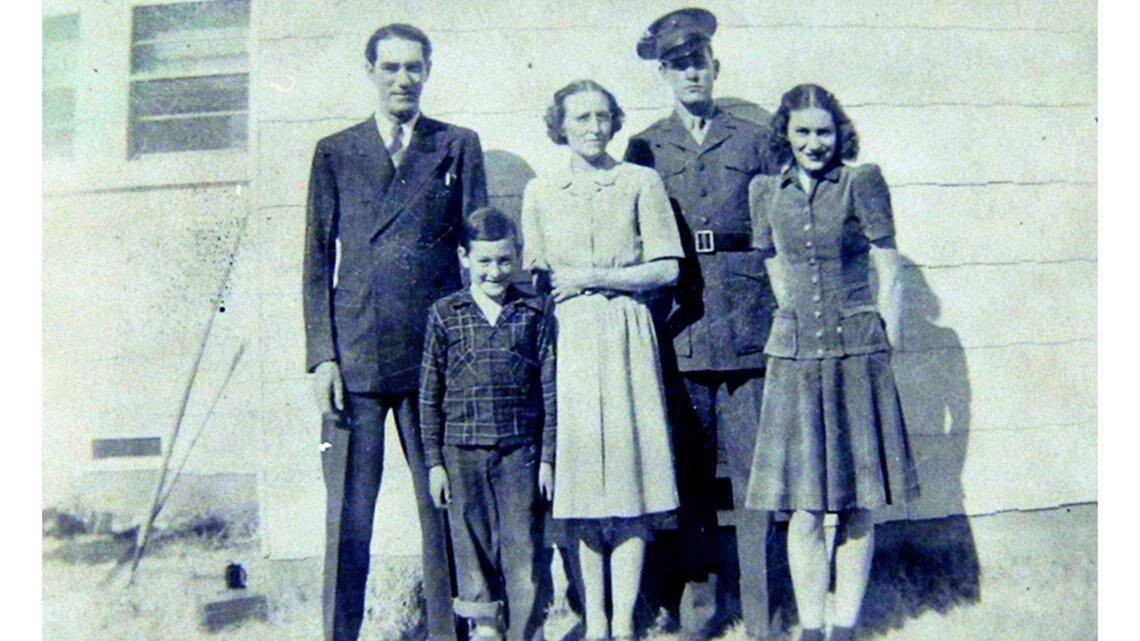

Sometime around Christmas, 1935, Ella became pregnant with her fourth child. It could not have been terribly welcome news to her or Lawrence (L.O), her husband, as things were already tight. Lawrence had struggled to retain gainful employment in recent years, bouncing from job to job, living from paycheck to paycheck, when there was a paycheck to be had.

L.O. and Ella Holley were people of faith. They were Baptists, in fact, and firmly ensconced among the membership of the thriving Tabernacle Baptist Church in Lubbock, Texas, where they made their home. Ben D. Johnson was the founder and pastor of the church, which opened its doors for the first time on March 12, 1933. In spite of – or maybe because of – the Great Depression, the church grew like a West Texas weed. Young couples like the Holleys flocked to the rapidly-expanding flock.

1936 was the year of The Great Heatwave. It remains the hottest U.S. summer on record. It was a miserable time to be pregnant and Ella was VERY pregnant during the hottest portion of the heatwave. July 1936 is the hottest month ever recorded in the United States. Ironically, during the early days of Ella’s pregnancy, February marked itself the coldest month on record. It was a year of extremes.

What joy must have filled her soul the day she finally delivered her fourth child, a healthy, bouncing, baby boy she and L.O. named Charles Hardin.

Ella felt like the name Charles was too big and formal for her little guy. She took to calling him “Buddy” and the nickname stuck.

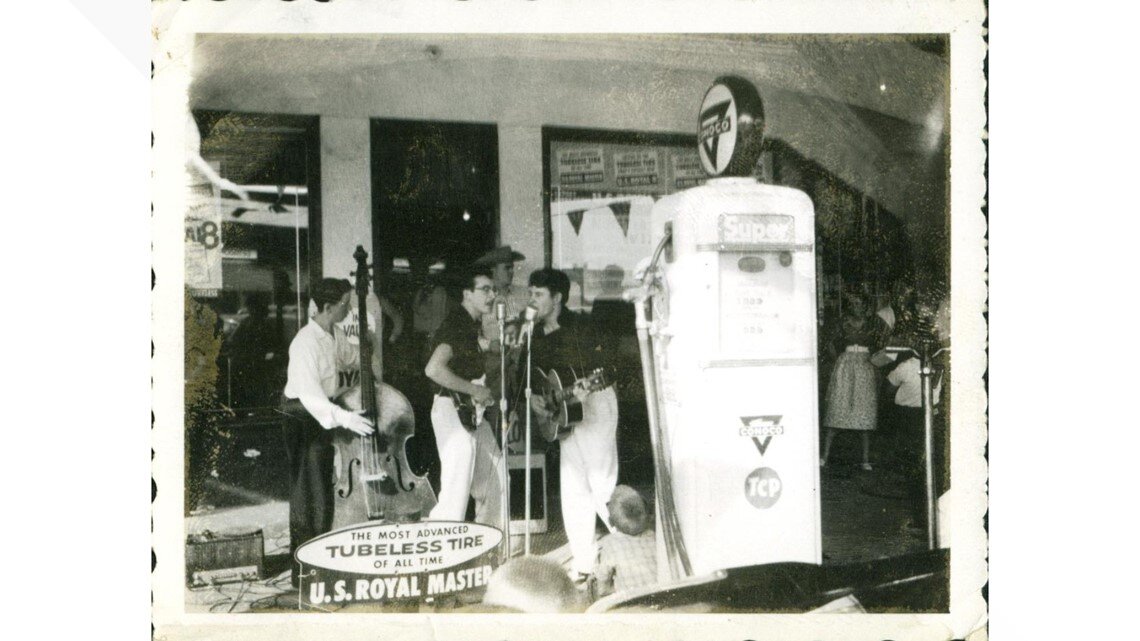

The Holleys were a musical family. Everyone but L.O. played an instrument. Buddy’s older brothers sang and played at various local venues and at church. But it was Buddy who would make his mark on the world, becoming a pioneer of 1950’s Rock and Roll and an American icon.

The little Baptist boy who was raised, married, and later had his funeral at Tabernacle Baptist Church in Lubbock delighted the world with songs like “That’ll Be the Day” and “Peggy Sue.” His career was cut short by the famous plane crash that took his life and also claimed musical upstarts Richie Valens and The Big Bopper. Don McLean, in his classic song “American Pie,” labeled it “The Day the Music Died.”

Buddy was just 22 years old when he died.

Buddy Holly (the spelling of the surname was changed from “Holley” to “Holly” on his first album) influenced rock and roll legends like Elvis Presley, the Beatles, Bob Dylan, and Elton John. The famous band, The Hollies, named themselves in his honor.

The little Baptist was born with wanderlust.

When Buddy was a young teen, Pastor Ben Johnson asked him, “What would you do if you had ten dollars?”

Holly answered, “If I had ten dollars, I wouldn’t be here.”

Still, the rail-skinny rebel who helped launch a genre never completely strayed from his faith or from his roots, which grow deeply in the windblown plains of West Texas.

Hope…

The longest stretch of consecutive Lubbock Christmases without snow was 28 years, from 1911 through 1938. The lack of Christmas snow, however, does not mean January doesn’t blow its bitter winds across the plains and chill even the hottest-natured local to the bone.

There was unrest in the world. Japan invaded China in 1937. Germany set its eyes on annexing Austria. The lines were being drawn and the seeds of a second world war sown.

The winds of war notwithstanding, each new year brings with it hope and 1938 was no different. The Great Depression was losing its grip on the country. Financially, things were “Better.”

Things got way better for Emil and Theresa on the fifth day of January 1938, when the brand-new year brought them a bright-eyed baby boy. They named him Emil Joseph, after his father and…well, Jesus’s dad. “Emil” is a Latin name meaning “eager.” Joseph is Hebrew and means “God will increase.”

Eager for better days and a brighter future, the couple welcomed their baby boy into a troubled world. He was born in Schulenburg, Texas, a little town halfway between Houston and San Antonio. Settled in the 1800s by German immigrants, Schulenburg claims it is “halfway to everywhere.”

Schulenburg may be halfway to everywhere, but it is a long way from Lubbock, which is where Emil and Theresa Holub moved their young family shortly after E.J.’s birth. That is what they—and one day the rest of the world—would call their little fellow: E.J.

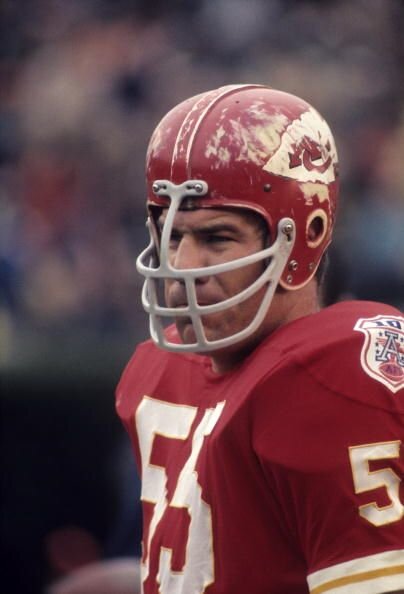

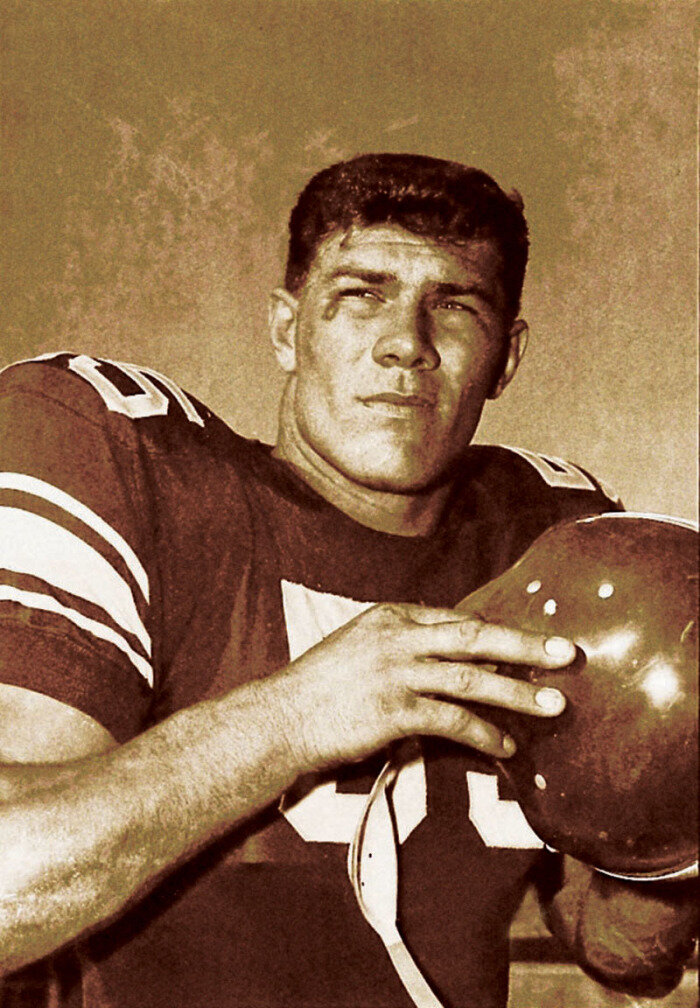

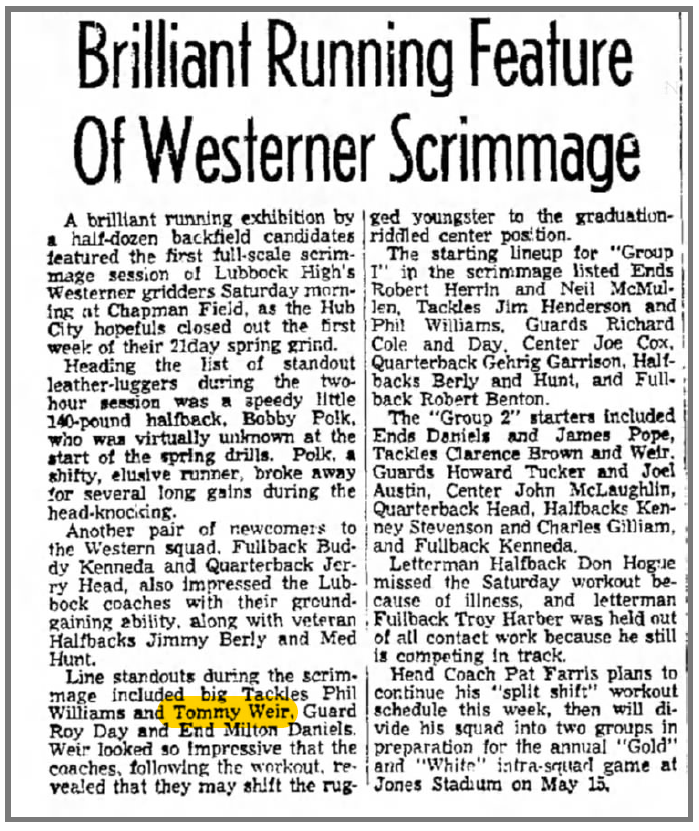

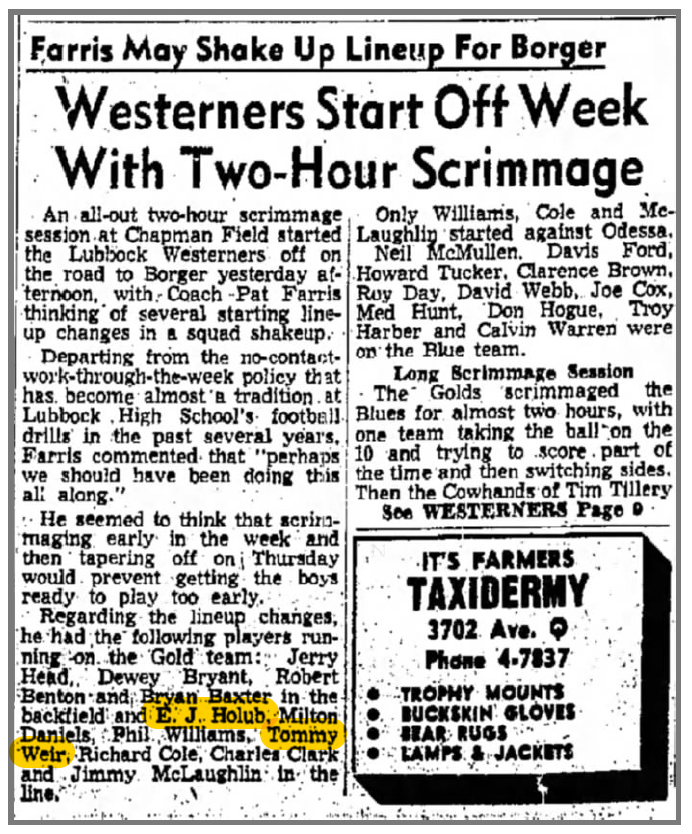

E.J. Holub would become the most famous football player ever to come out of Lubbock High School. A ferocious competitor and supreme athlete, he lettered in football and track and field. Upon graduation, he attended Texas Technological College, which would later become Texas Tech University. He played both ways, as an offensive lineman and a linebacker. His teammates nicknamed him “The Beast.”

As a senior at Tech, he had 15 unassisted tackles and eight assisted tackles against Baylor. Against Arkansas, he racked up 18 unassisted tackles and returned an interception for a 40-yard touchdown. His number 55 was the first number ever retired by Texas Tech. He was inducted into the Texas Tech Hall of Fame, the College Football Hall of Fame, and the Texas Sports Hall of Fame.

In 1961, the year of my own birth, pro football was divided into two leagues, the old NFL and the new AFL. Dallas, Texas, was home to two teams, one in each league. The AFL’s Texans came first, in 1960. In 1961, Clint Murchison secured the right to launch an NFL franchise in Dallas. He called his team the Cowboys. The Texans picked E.J. Holub sixth overall in the AFL draft and the Cowboys selected him 16th in the NFL draft. Holub elected to play for the Texans and owner Lamar Hunt. The next year, Hunt moved his team to Kansas City and renamed them the Chiefs. Holub started on both sides of the ball at the beginning of his AFL career, as he had done since high school, playing center on offense and linebacker on defense.

In 1964, Holub had surgery on both of his knees. A series of knee and leg injuries would mar his career, but would not stop him from becoming the only player in NFL history to start on both offense and defense in TWO Super Bowls. The Chiefs lost Super Bowl I to the NFL champion Green Bay Packers and their legendary coach Vince Lombardi. In Super Bowl IV, Holub’s Chiefs defeated the Minnesota Vikings, 23-7.

Holub underwent 20 knee surgeries. Eleven of them occurred while he was still playing – six on his left knee and five on the right.

A reporter once saw Holub’s knees in the locker room and commented,

“It looks like you got into a knife fight with a midget.”

Playing much of his career through immense pain, Holub was always a team leader—what he called “a holler guy”—and a perennial All-Star, being named to the AFL All-Star team in 1961, 1962, 1964, 1965, and 1966. He retired in 1971 and was named to the Kansas City Chiefs Hall of Fame in 1976.

The football legend and favorite son of the Lubbock High Westerners died at his home in Midland, Texas, on September 21, 2019. He was 81 years old.

and Love…

About the time Ella Holley delivered Buddy, friend and fellow Tabernacle Baptist Church member Mattie Lila became pregnant with her fifth baby. She already had three sons and a daughter, but she and husband J. O. Weir were making room for another. Nine months later, while little Buddy was learning to stand on his own two feet and trying to toddle, J.O. and Mattie were saying hello to their fourth son, Thomas Henry.

L.O. Holley and J.O. Weir were deacons at Tabernacle. Their boys, Buddy and Tommy, would grow up together in that church and its tight-knit community. The boys formed a friendship that lasted through middle school and into high school when their interests began to pull them each in a different direction. Buddy pursued his musical passion. He even tried to compel Tommy to pursue it with him.

Tommy was into football.

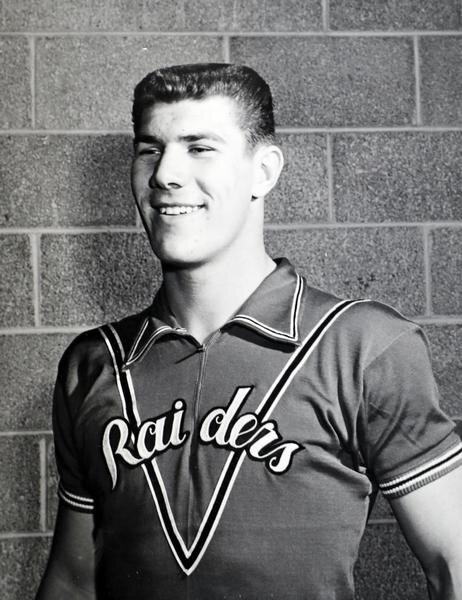

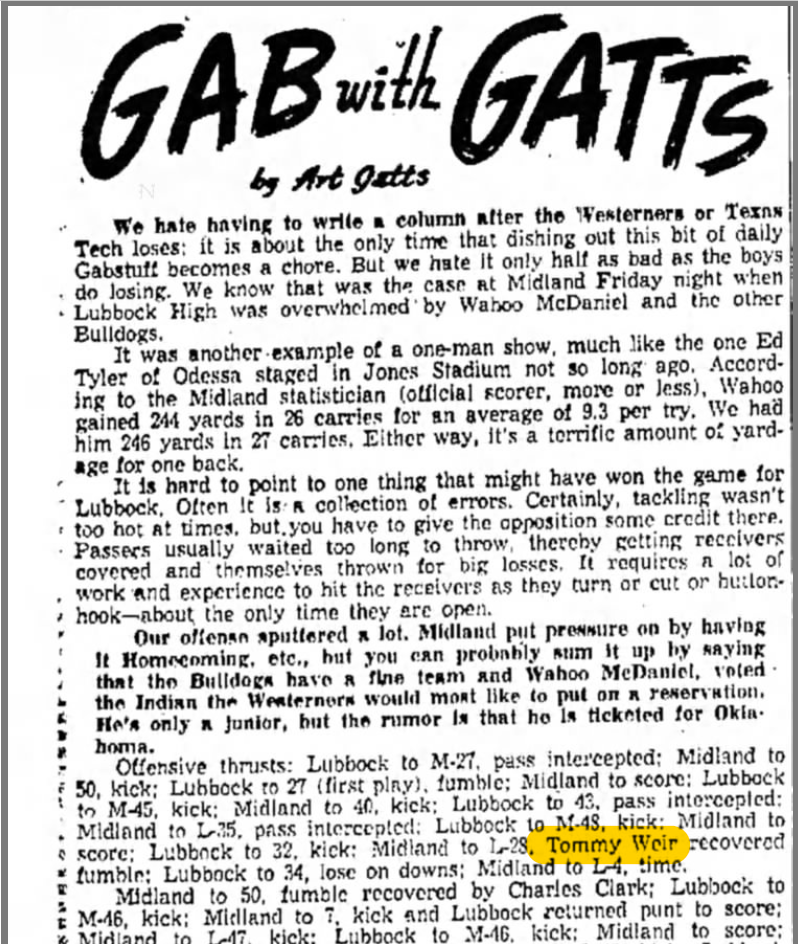

The families became more intertwined when the eldest of the Weir boys, John Edward (J.E.), married Buddy’s older sister Patricia Lou in 1948. Tommy and Buddy were all but Brothers… from different dads. and different mothers. Football led Tommy to form a friendship with another kid bound for stardom. He played on the defensive and offensive lines for the Lubbock High Westerners alongside the emerging legend, E. J. Holub. Weir and Holub anchored the team’s most dominating units. Since Tommy was a year and a half older than Holub, their football careers would only overlap for a season at Lubbock High.

Upon graduation from Lubbock High School, Tommy enrolled at Texas Tech, where he joined the Tech football team.

There was another pull upon his soul, however, that was stronger than football, stronger than Lubbock, stronger even than Texas Tech. Tommy recognized God’s calling on his life to full-time gospel ministry. He married his sweetheart, Mary Louise Howard, and together they moved to Chattanooga, Tennessee, to enroll at Tennessee Temple University.

That decision would lead to an odyssey, a ministry spanning a half-century that included pastorates in Lubbock, Texas, and Walsenburg, Colorado. Ultimately, it led to the role of a lifetime as the Associate Pastor to Dr. Earl K. Oldham and the Calvary Baptist Church in Grand Prairie, Texas. Tommy served under Oldham until Oldham’s retirement in the early nineties, at which time Tommy assumed the leadership of Oldham’s Prime Time Sunday School class. Tommy led the class until his own retirement in December 2020.

The greatest of these…

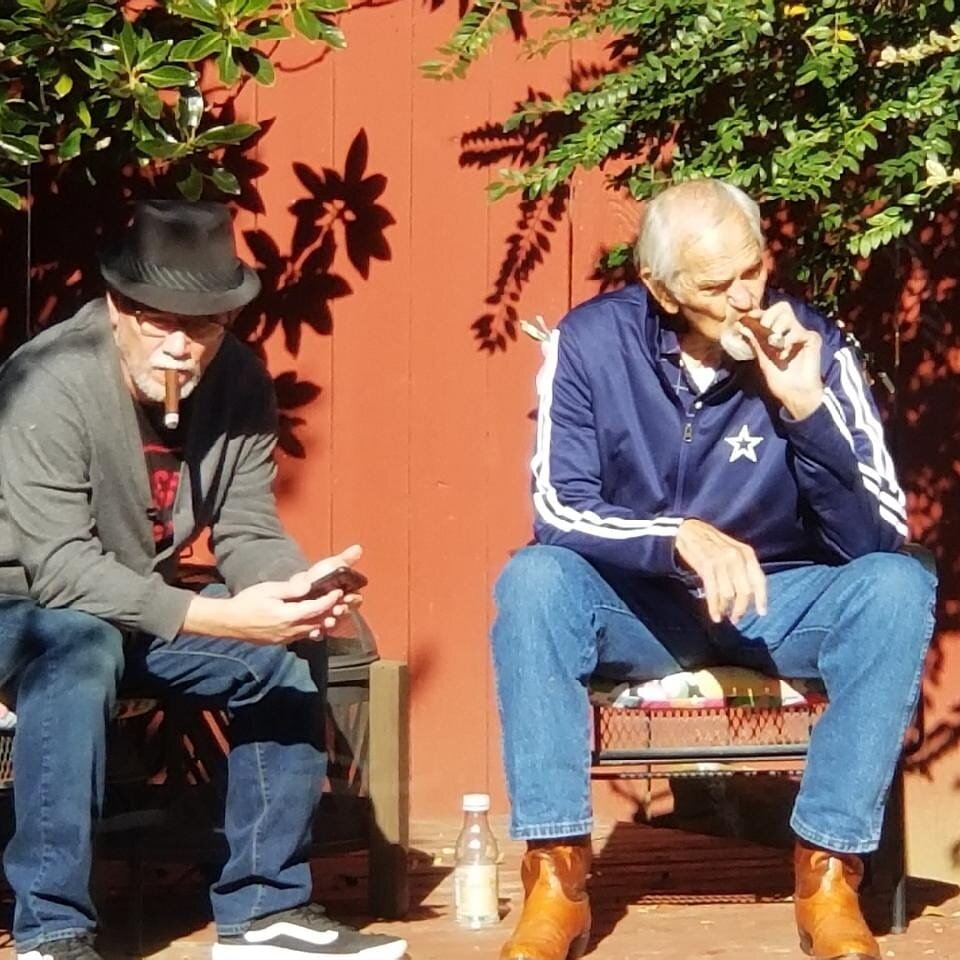

Tommy could sing, but not like Buddy Holly. He could play football, but not like E.J. Holub. He could, however, love like no other. Still can.

He could also intimidate with the best of them.

I met Tommy in the Fall of 1979. I was dating his daughter, Donya. She had come down from Walsenburg to attend Arlington Baptist College… and to escape the oppression. of small-town mountain life. She was staying with Tommy’s older sister Doris and her husband Paul. Tommy was scheduled to come through town on a truck-driving mission. He had taken a long-haul trucking job to augment his income, since the tiny Walsenburg church could not adequately pay him to sustain a family.

Dating Donya was considered hazardous business, both in Lubbock and Walsenburg. That news had not reached Arlington in time to prepare me.

When I first saw Tommy Weir, he was seated at the head of Aunt Doris’s table, eating a bowl of chili (I think it was chili). He was a mountain of a man with a mountain man’s beard. He stood 6’4 and was north of 350 pounds. By contrast, I was 5’10 and weighed in at a buck forty-five.

Donya introduced me. He scowled at me, said nothing, and turned his bowl upside down on the table. He continued eating his chili… right off the table… with his fingers.

It was an unusual and unexpected move. I was taken aback, thrown right off my game… and that’s an understatement. The better part of wisdom would have been to excuse myself, run away, and not look back. The better part of wisdom, however, has pretty much escaped me my entire life.

I do not remember much about the conversation after that. I think things softened up after everyone had a good (aka, nervous) laugh about the chili incident. I do remember the relief of watching him climb into the cab of his semi to leave for Houston or wherever. I also remember thinking a guy that size belonged behind the wheel of a truck that size. That Peterbilt fit him the way a Chevy might fit a mortal.

The rockiness of our relationship would continue for some time and gain intensity after Tommy and the rest of the family moved to Arlington and Donya moved back in with her parents.

I was an impetuous preacher boy with more ego than sense. I once angered him by calling him, “Brother.”

I thought it was innocent. I called everyone “brother.”

He informed me, “I am not your brother. I am her father. You will call me Mr. Weir.”

Geez.

There were other incidents over the ensuing weeks. They culminated in his literally tossing me out of his house and telling me, “If you ever see my daughter walking down the street, you better turn around and walk the other way. Don’t even look at her.”

I drove away, wiping tears of frustration and anger. Ten minutes later, I returned, knocked on the door, and informed him, “You can throw me out all you want, but you can’t make me stop loving your daughter.”

We turned the corner that day. I became a son to him. When I asked for Donya’s hand while she and I were both just 18 years old, he readily agreed and embraced me. He told me he couldn’t want a better son-in-law than me.

That is Tommy in a nutshell. Bigger than life. Bombastic. Mercurial.

More than anything, he loves out loud and without restraint. By the way he loves, you could not tell which were his kids and which were married to his kids.

The year is 1995. I am the pastor of the Victory Baptist Church in Paris, Texas. Tommy is on staff at Calvary Baptist Church in Grand Prairie. We have had some sort of dispute. Over what, I do not recall. Angry words have been spoken between us and this cloud of enmity hangs like a blanket over East Texas.

Sometime after midnight, there is a terrible banging at my front door. I leap from the bed, sure something terrible has happened to someone, somewhere. Door-banging after midnight at a

A minister’s house never means good news. Someone has probably died. If not, someone is about to!

I open the door to find the ominous figure of Tommy Weir filling the doorframe and blocking out the night behind him. He grabs me, bearhugs me, and weeps.

“I’m sorry, son. Please forgive me.”

The thing is this: I am pretty sure he was not the one in the wrong. He just refused to let another day dawn until he had reconciled with his son-in-law. His… son. He drove 125 miles in the middle of the night to make things right, even if it meant saying he was wrong.

That is just one of the things I have learned about love from the man who counted Buddy Holly and E.J. Holub among his friends. To him, no one counts so much as Jesus, and nothing matters more than loving the people he loves.

And now abides Rock and Roll, the NFL, and the gospel…

And now abides faith, hope, and love…

And the greatest of these…