How an old Baptist preacher took his morning coffee and started me thinking

I was raised on biscuits, beans, barbecue, and Baptist preaching. My grandfather was a cotton farmer-turned-Baptist minister who did not leave the cotton field to harvest souls until he was 40. West Texas hammer-fisted, hard-boiled, Hellfire-and-brimstone preachers influenced him.

Thus he was influenced. Thus he became.

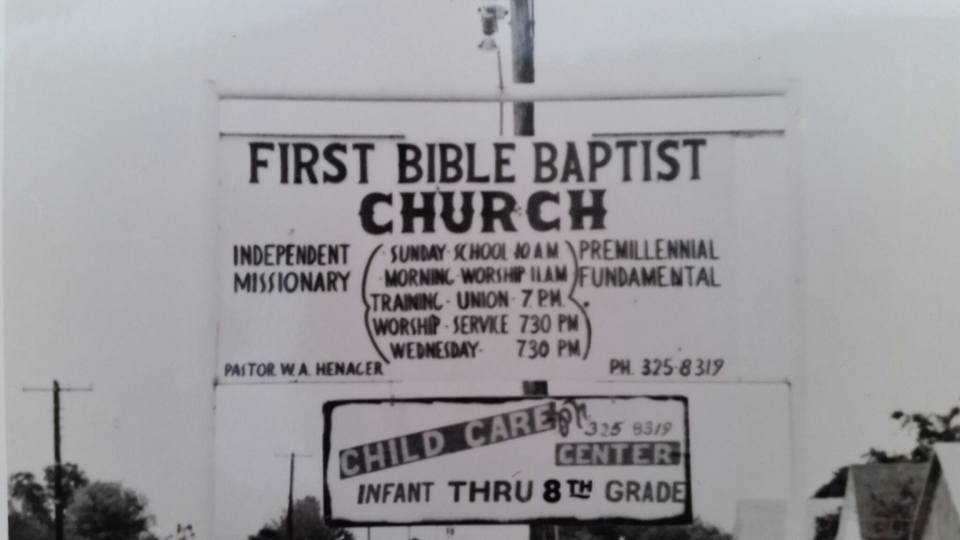

I have known hundreds of preachers. Pastors, missionaries, and evangelists rambled in and out of my life in my formative years, each leaving his mark. Yes. “His” mark. We had no women preachers in our independent, fundamental, pre-Millennial, Bible-believing, Bible-preaching bunch. Well, not officially, anyway. None of the other sexes, either. I was unaware there were more than two sexes but that’s another story.

Ultimately, I became what I beheld. I am satisfied that that was the right thing to do. I had the call of God on my life, the gift of preaching/teaching, and that became my path, profession, and passion.

Preacher, yes! But not like other preachers

My grandfather, whom I called Big Granddad, was unlike the other preachers I knew. His personality was rock solid but not grandiloquent. He did not fill up a room. He never made it about himself. For all of his size and strength, for all of his passion and commitment to the gospel, he was not the shouting kind. His sermon delivery was low-key. Sometimes, you had to lean in to hear what he was saying. He was not eloquent like some, not showy like others. Instead, he was sincere and earnest and completely authentic in his faith, even if it tended toward the absurdly conservative and restrictive.

A Scene from a Coffee Shop

Big Granddad aged, of course, and I witnessed it, sometimes from afar, other times nearby. A new century commenced and he was in his eighties, facing the twilight of his life. The man I always saw as oxen-strong was feeble and could no longer control his diabetic feet well enough to drive. My grandmother was determined not to let him rot or fade away, so she drove him to the coffee shop adjacent to the Holiday Inn to get his morning coffee and enjoy a change of scenery, a break from gazing out the dining room window to the empty field he once commanded with the skill of a master gardener.

I lived nearby and dropped in to see him one morning. Granky (the name I saddled my grandmother with when I was a toddler and learning to talk) told me he was at the coffee shop and that I should join him there. I said I would.

The coffee shop is nondescript in my memory, just another roadside diner that may have once been an iHop or something else. There is a bustle in the place. Over there is a family clearly passing through to somewhere more fun grabbing breakfast before hitting the road. A local doctor or drugstore chemist buries his face in the Dallas Morning News while his coffee cools to lukewarm.

“Sit anywhere, hon,” the waitress says as she passes by to warm up the newspaper reader’s coffee and take the vacationers’ order.

I point to the lone, gaunt old man with receding, slicked-back hair that is surprisingly not completely gray, dressed in a white dress shirt, blue tie, black slacks, and suspenders. He hunches over a steaming cup of coffee

“I’m with him.”

She nods.

Before I made my presence known to Big Granddad, I watched him for a minute or two. Sitting at a table not far from him are two locals – men somewhere between my age and Big Granddad’s age. Maybe they were 60ish or perhaps still in their fifties. I recognize them, not as men I know but as the kind of men I have known my entire life: small-town, rural men with the work ethic that built America. I knew instantly that they were men of fortitude and faith. They were family men who loved their people but probably seldom said so. You just had to know they loved you by their deeds. Their words were few until each morning they were together to talk about the day ahead, the days just passed, and the days long since forgotten by most. They talked politics and preachers, trucks and tractors, the weather and the weatherman, stingy soil and failing crops, and old man so-and-so who just passed and left his poor widow all alone on a hard planet. They worked out which would look in on her and which day.

One was tall, very tall. I would put him at 6′ 7″ or better. He was lean and wiry. His skin was rawhide and his wrinkled face wore sunspots. Like Big Granddad, his hair was slicked back. The imprint of the Stetson he wore when he wasn’t indoors left its pattern in his hair and on his forehead. The silver-gray stetson with sweat stains about the brow hung dutifully on the post of the vacant chair to his right. Cowboys don’t wear hats indoors. I gave him a name right then and there because I knew I would not ask it. I called him Billy Wayne, after a cousin of Mom’s I met once out in Abilene when I was a small boy. He was tall, too, and certified Texan.

The other fellow was not short, except as you compared him to the tall one. I imagine he was 5’11 or maybe 6′. Hard to say since he was seated. He had heft to him. I would not classify him as fat but his fighting weight surely put him in the heavyweight division. He was dressed more like Big Granddad but with a sportscoat. His fedora hung on the post of the other empty chair at the table. It was black and I envied him. I have always had a thing for fedoras. I assessed Billy Wayne as a farmer with almost absolute certainty. The hefty fellow I named Joe Eddy, after one of my father’s friends, Joe Eddy Taylor, a member of the Taylor family back In Mineral Wells, where I grew up. This guy did not resemble Dad’s Joe Eddy, who I remember as thin. But he looked like the name would fit. I imagined his father was a small-town doctor with big-time dreams for his son, and thus named him Joseph Edward, a fine name for a man going places. East Texas kicked that dream down a notch and shortened his regal monicker to Joe Eddy. I suspected he went to used car auctions to populate his carlot somewhere on the edge of downtown.

I gave them names and a backstory before I sat at the table with Big Granddad, not ten feet from theirs.

I also noted that my grandfather, never a man to start a conversation or impose himself on strangers – or anyone unless it was Thursday night and he was out soul-winning, seemed to be enjoying the geeing and hawing of the odd-couple friends.

I would never say he was eavesdropping. For one thing, his hearing was not great. I think he was soaking up the vibe. There was a tone to the banter that suggested long-term friendship and lighthearted prodding. I doubt either man was ever wittier than at breakfast with the other.

There was an ease in their friendship that radiated like the first rays of the morning sun on a cornfield. There was a cadence like the crackle of an evening campfire on a Spring roundup or summer rain drumming on a tin roof. I think it took him back to when his body was virile and strong, his mind was nimble, and his spirit was charged with the fire of the living God.

“This seat taken?” I asked BG as I sat down.

“I saved it for you.”

If he was surprised to see me, it didn’t show.

“The coffee good here?”

“It beats not coffee.”

Kickstarting a conversation with BG is like starting an old tractor that has sat too long in the field.

“You know those fellows, Granddad?”

“I don’t recall.”

Nothing was truer than that. He didn’t recall plenty by then. He was not yet in the throes of the dementia that would later claim him but he was mired in forgetfulness.

“They seem like nice fellows, though,” he added.

I agreed.

Conversations in my Head

I will never know what Billy Wayne and Joe Eddy talked about. I would have liked to have introduced myself and my grandfather and maybe opened an opportunity for him to have companions with which to share a morning coffee. I didn’t because, although I am like my gregarious (and long-deceased) father and can talk to anyone, I am also like Big Granddad and will not.

The only bit I heard was toward the end of their morning routine at the coffee shop.

“Anything else, boys?” the waitress asked them.

“We’ve wasted enough daylight already,” answered Billy Wayne.

“Who’s turn is it to pay?” she asked.

They each pointed at the other and answered simultaneously, “His.”

I grinned and she smirked.

“I’ll figure out whose tab to put it on. I ought to put it on both. You’d never know.”

They were donning their hats and nodding to BG as they passed.

“Nice fellows,” I said.

“I might have witnessed to one of them once,” BG answered.

By “witnessed” he meant he may have talked to them about Jesus and salvation.

He may have.

I have been immersed in lively conversations in my head all my life. Maybe you have, as well. Maybe everyone has. Some of the best conversations I ever had involved no one outside myself. When I was four my imaginary friends were Big Ricky and Little Ricky. Mom set plates for them at the dinner table and never shut the door until we were all in the house. She was a good mom like that. I wish I could have kept them. I wish I knew what became of them or even what they looked like.

It’s been nearly a quarter century since coffee with Big Granddad. Looking back on it, I think I met Big Ricky and Little Ricky again in the form of Billy Wayne and Joe Eddy.

Expect to read conversations between them from time to time. I plan to eavesdrop and report their musings, fussings, wisdom, and folly verbatim.

As for Big Granddad, he was one-of-a-kind. He never owned much or made much money but when I needed a co-signer on a car, his word was gold and no banker ever said otherwise.

“Granky says I should give you a ride home.”

“I’d rather go fishing.”

Me too, Granddad. Just one more time”¦with you.